Ever wonder about tugboat tea?

Last night at Bridge & Tunnel, we asked: what does it mean to wonder? Ninety minutes later, we'd explored wonder as emotion, metabolic process, foundation of freedom, and the thing schools systematically kill. We debated whether the internet destroys wonder or amplifies it, why some people choose willful ignorance, and at what point water becomes water. Also, Seth's tea is apparently very stochastic.

The conversation touched on several interconnected themes—about curiosity versus awe, imagination as what makes us human, wonder as calibration, and how we metabolize experience. Here's what emerged.

Wonder as Central and Mysterious

Seth opened by suggesting that wondering might be both central to and mysterious in human experience. Is wondering an emotional disposition? Art, science, and social connection—despite their differences—all seem to have wonder at their core. Is wonder fundamentally an aesthetic experience? We feel wonder, terror, delight. These feelings can move us to act in the world. But is it just aesthetic? Or is there something more?

Wonder can move us to do things—but to do what? Is this something that comes from us, or are we struck with it? If someone says "I wonder" and it provokes wonder in you, is that the same wonder?

Dale was thinking about curiosity and awe—being awestruck is a kind of wonder. It would be a terrible life without wonder. Curiosity and wondering involve sitting back and reflecting.

Seth asked: what actually is it? Is it curiosity? Is it awe? Bewilderment? What do these things have in common?

Wonder as Connection

Lauren has been thinking about this question for awhile. She’s the one who brought it to the table so to speak. And she keeps coming back to the significance of connecting with other people. Maybe wonder is an external experience—like light shimmering on water—that creates connection we can share with others. Curiosity might be this desire to share with other people.

Seth pushed: does that connection come from an external place?

Lauren thought it's a shared experience. Knowing others share the connection—the sense of being connected is a deep part of what makes wondering possible.

Ryan connected this to empathy and love—they compel the soul and spirit, and everything relates to that. He was thinking about whether wondering recognizes deep relationship and interconnection.

Seth asked why that parallel exists—why are empathy, connection, and love related to wonder?

Ryan responded that it's a kind of harmonizing—an operation of consciousness that moves toward order and structure, but it's felt. This might be the aesthetic connection Lauren was pointing to. Instead of explaining the light on the water, we engage and commune with it.

The question leaves us to “wonder” can we ever really know it's the same as what somebody else is experiencing?

Imagination and What Makes Us Human

Kaarina offered the group to try out this idea: Aristotle said humans are rational. Sartre didn't like that. Sartre suggested imagination defines us—seeing things as other than they are. We recognize our limits and start asking what would it be like if we couldn't imagine.

The group explored autism, processing, and imagination for a while. Part of what we do when we imagine is we overcome selfness. If wondering is a leap into the world—then what?

Ryan added: and a willingness to be wrong and reach out.

Seth suggested wondering might be projection out into a variety of realms. Awe and puzzlement—why do we do this?

Kaarina mentioned wondering is the foundation of freedom. If you can't imagine, you can't see other choices. And those choices are what make freedom possible.

Wonder as Metabolizing Experience

Andrew brought up why he seeks experiences of wonder. He thinks it's a kind of calibration he can feel building in his body. Without wonder, he doesn't live in a state of wonder—but he seeks exposure. He loves camping, hikes, surfing. If he goes too long without it, he can delude himself into accepting the mundane as the whole. Wondering is like a kind of remembering.

He was thinking about everyday experiences as a kind of basic function, like metabolization—kind of mechanical, which was disappointing to him.

Seth said sure, there's probably a kind of science to it (neurons and chemicals). But it seems like self-consciousness without wondering is impossible.

Ahsha loved the phrase "metabolize experience." She was thinking about people who don't wonder—it reminded her of her family. No wonder, just the routine and tasks that need to be accomplished.

This brought up the question: why do some people choose willful ignorance?

Andrew clarified he meant metabolizing experience had a negative connotation for him. Going through life with a rote function that never examines the experiences

Asha saw it as positive. She really loved the phrase and was thinking that when people aren't present, aren’t wondering, they don't metabolize their experience. Wonder is what makes that processing possible, maybe like an enzyme.

The Internet Debate: Does It Kill Wonder?

The idea was raised that the internet’s easy access to answers was a prime villain in diminishing wonder.

Bob said absolutely not. He feels like people say this all of the time. He’s fascinated that Australia banned social media for people under 16—how are they ever going to enforce that? Kids can just use their mom's account.

And furthermore (I kind of wish I had the soap box on hand last night) the idea that the internet is there to provide all the answers and that kills wonder is totally WRONG. He mentioned dcode.fr as an example. He called it an ugly cite, but a wonderful tool. It brute forces solutions and comes up with as many different answers as possible to a puzzle. Every time he looks up something, he has another question about that information. It opens up more possibilities for wonder.

Ryan asked: is questioning and wondering the same thing?

Lauren wanted to understand Bob’s point in relation to human connection. She said, what you're talking about sounds good, but you're still dealing with a machine. The internet has meaning, but how do we translate that to relating with other people?

Bob admitted: I'm a contrarian. I disagree to explore. He doesn't think banning devices in schools is good. The idea that before people didn't know things they had to look them up in a book—as if the book was some kind of holy grail of better answers than the internet. He looks things up with 27 different kinds of AI because he's curious.

Kaarina added that she's a contrarian too. When you go to the internet, you're not not going to other people. The information on the internet is from humans. Bob is confusing algorithms by asking different questions, but all the information he's pulling up is still a kind of relationship with a human—in the same way that reading a book creates a relationship with an author. It's just a different kind.

Loren: So how does that change the way you relate to people?

Bob: It doesn’t.

Willful Ignorance and Schools That Kill Wonder

The group was getting excited at this point, so we had to start directing traffic.

Andrew brought up a scene from the movie While We're Young where two couples, a younger an and an older couple can’t remember something. One character wants to look it up right away and the other says,"Let's not.” I don’t know about you guys, but my brain just assumed it was the older couple saying, let’s not. However, the story apparently revolves around a younger generations rejection of easy consumption. Here’s a clip of what Andrew was referring to:

Bob didn't like that at all. He wants to know the info right away. This was endearing and got a good chuckle from the group.

Jan brought in that schools seem to have kids in them who are wondering less and less over time. She was making a connection to the internet’s quick answers and children seeming less engaged in the world.

For Kaarina, philosophy of education is one of her specialties. And she brought up that three and four year olds today still have a giant sense of wonder. It's natural for humans to wonder. School is where we kill the love of learning. We kill the sense of wonder. It's a place where kids are trained to look for one right answer, and that crushes curiosity.

Stochastic Liberation of the Binary (and What Kind of Tea Seth Drinks)

Ryan was thinking there's a difference between wonderment and seeking quick responses to questions. Wonder opens up. Seeking funnels down.

This got Tanya thinking about how artists are taught critique—something opens up like a question like why is the sky red? Or how does an anemone live. And then there's this part of us that's predictive, wanting to fill in answers. Wonder reminds us to be curious when we need to stay more open.

Seth brought up what became the not-fifty-cent phrase but the two-billion-dollar phrase of the night: the stochastic liberation of the binary.

Ryan was like, "Oh yeah, binary is a mistake.” And Ahsha was like jump back jack, what the heck are you talking about Seth?

Seth made his first go at explaining what stochastic means, Brownian motion is. But he used the example of steam coming off the surface of a cup of tea. There was a lot of laughter about what kind of tea Seth might be drinking that the steam might be so stochastic. Perhaps the tea might be on the tugboat that Asha just got off of.

But it wasn’t just stochastic in this phrase, Seth had to unpack liberation of the binary as well: The disruption of binary through spontaneity—by virtue of acting upon itself in perpetual activity. There's a connection to the character of what there is in the world. It may not be predictable, but it can make you feel both minuscule and vast at the same time.

We got down to the idea that it's random in a dynamic way, that is disruptive. And Kaarina gently corrected that it's not completely random—it's more like branches or rhizomes of a tree.

I wish I could tell you what point Seth was making in relation to the Stochastic Liberation of the binary, but I was lost track a little while trying to map out a thought of my own.

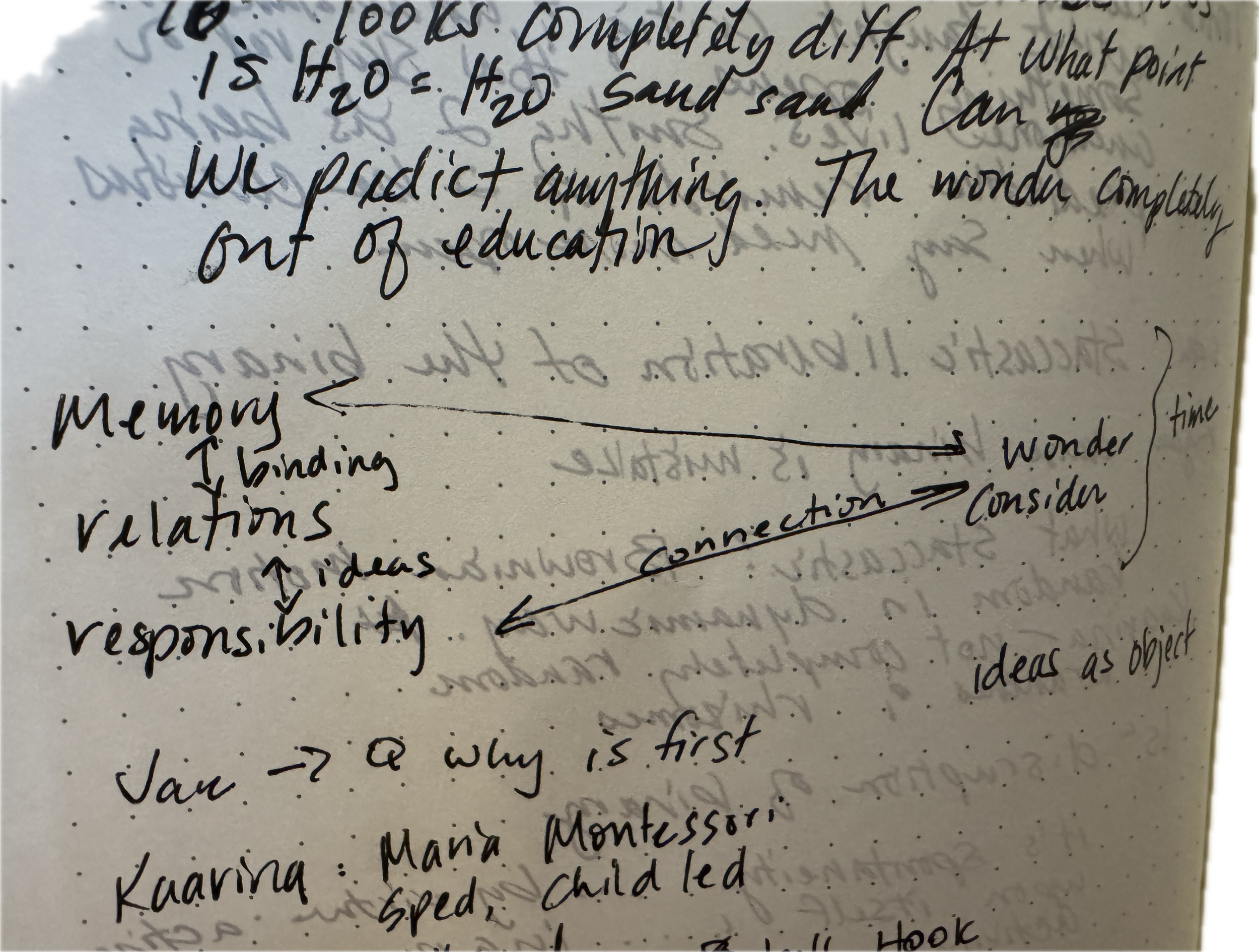

Trying to figure out the relationship between some ideas about wonder.

Wonder at the Scale of Atoms

Bob wanted to make sure he wasn't giving anybody the impression that he stops wondering when he gets information. He's always worried when he's teaching—when we're passing on knowledge—about how powerful that is and what he's doing when working with kids.

He believes we're in the midst of a Kuhnian paradigm shift (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/thomas-kuhn/#ConPar)—a mind-boggling alteration in how we understand the world works. As a retired chemical engineer who was always bridging the micro and the macro, the idea that we can explain the world by invoking what we can't see—an atom is very, very small. No human mind can possibly picture it. There are more atoms in a grain of salt than all the stars in all possible multiverses. An atom itself has no color or shape, nothing that makes sense to us. But if we take 10 to the 23rd atoms or so, it looks completely different.

At what point is water water? At what point is sand sand? We can't predict anything from the micro level. This is amazing and wonderful.

And wonder has been completely edged out of education.

What We Think We Know

We found ourselves talking about Maria Montessori and child-led learning. About how our wonder and how we consider things is part of our connection and responsibility to each other. The way we relate to each other, to our ideas, to memory.

So what does it mean to wonder? We explored it as emotion, aesthetic experience, metabolic process, calibration, foundation of freedom, and the thing that makes imagination—and therefore choice—possible. Wonder opens up where seeking narrows down. It connects us to each other and to the world at scales from light on water to atoms in salt grains. Schools kill it systematically. The internet might amplify it or might numb it, depending on how we use it.

And somewhere in there, Seth's tea steam performed its own small act of stochastic liberation.

Come wonder with us next Wednesday. We'll be exploring why people are religious.